In What Way Are the Teachings of Plato Reflected in the Art and Architecture of Ancient Greece

Greece

By Sally Mallam

Contributing Writer

Something boggling in the history of humanity occurred 2500 years agone in Athens—much of our cultural heritage, for better and worse, descends from a very small population of landowners, farmers and sailors during a surprisingly brusk space of time. They organized themselves into a radically democratic regime. They held as a loftier ideal the dignity and freedom of an individual free man. They produced sculpture and compages which prepare the standards by which these arts are however measured, and they laid the foundations of our philosophy, mathematics and sciences.

Stepping from a aeroplane in Memphis in 1968, Robert Kennedy was informed that Martin Luther King had been assassinated. In an impromptu moment that has become famous, he responded:

"… My favorite poet was Aeschylus. He once wrote: 'Even in our sleep, pain which cannot forget falls drop by drop upon the heart, until, in our own despair, against our volition, comes wisdom through the awful grace of God.'…. Let usa dedicate ourselves to what the Greeks wrote so many years agone: to tame the savageness of human being and make gentle the life of this world."

To come to an appreciation of our Greek heritage is in some fashion like to a fish coming to an appreciation of water.

Students are often astonished when they read for the first time the literature of classical Athens. It seems so much more familiar than, say, Dante's Inferno, although this was written almost 2000 years afterwards in a language much closer to our own. Greek plays were different anything the earth had seen earlier. They are gory, horrific, passionate and heart breaking, their characters display human nature at its best and at its worst.

It is the Greek method of thinking that the Western globe has inherited. The rediscovery of Greek scientific discipline and philosophy in Medieval Europe kindled the Renaissance. To come up to an appreciation of our Greek heritage is in some way similar to a fish coming to an appreciation of h2o. How we report this legacy is itself a production of that legacy. We separate our search for knowledge into Greek categories, such as politics, philosophy, history, and the individual sciences. Even the words we utilise for these disciplines are typically taken from the words used by the Greeks – technology, economics, logic, even our give-and-take "schoolhouse", taken from the Greek schole.

By the beginning of the sixth century BCE, Athens was disrupted by the aforementioned social unrest that had afflicted many of the poleis (city-states). Farmers, many of whom were Hoplite soldiers, banded against the aristocrats and ceremonious war seemed unavoidable. Additional tensions were caused past the lack of written laws. To the Greeks, justice as role of a cosmic order ruled even the gods, just in fact the aristocrats controlled the laws and could change them at will. In 594 BCE they tried to preclude the civil war by electing the poet Solon as Archon, with a mandate to reform the constitution.

Solon (638–558 BCE)

Solon

Solon was certainly one of the first Greek Axial thinkers we know of; he traveled widely in Greece, visiting Croesus in Lydia, and Thales in Miletus. Co-ordinate to Plutarch, Solon was "not an admirer of wealth," but a "lover of wisdom" (Philosophia). Similar Thales, he spent time in Arab republic of egypt, where, according to Plato, he heard the story of Atlantis from Egyptian priests.

Solon told the Athenians that their unstable political situation could not be blamed on a divine cause but was the upshot of homo selfishness. All citizens, he said, should have responsibility for this dysnomia (disorder). In his view the solution lay in their hands, and only a collaborative political try could restore Eunomia – good order and stability. Eunomia was about balance. Information technology meant that no one sector of society should boss the others.

The Areopagus, every bit viewed from the Acropolis, is a monolith where Athenian aristocrats decided important matters of state during Solon'due south fourth dimension.

He set about reforms that strengthened the rule of law and set Athens on the road to commonwealth. For example, he abolished debts incurred by and large by farmers and debt slavery, and formalized the rights and privileges of each class of Athenian guild co-ordinate to wealth. Wealth not birth would exist the criterion for access to public office. He created a serial of census ratings according to which each adult citizen would have his wealth recorded and thus have access to offices. Under Solon a comprehensive lawmaking of law was spelt out and made available on tablets, so that citizens could see how they were governed and what their rights were.

Under Solon a comprehensive code of law was spelt out and made available on tablets, so that citizens could see how they were governed and what their rights were.

Solon set up a new standard as an ideal denizen when he refused stay on to establish a tyranny in Athens to enforce these reforms: he had served the people without personal reward and equally their equal. All the same, his reforms and ideas were non immediately accustomed, and after his departure, Athens lapsed once more into factional fighting and anarchy. Notwithstanding, the Greek globe was impressed and put Athens at the forefront. In improver, the thought of Eunomia would influence non only political development simply the evolution of early on Greek scientific discipline and philosophy.

In 561 BCE, Pisistratus fabricated his first attempt to become tyrant of Athens (a term that meant simply aggressive men who seized power), but failed. On his third attempt, fifteen years later, he entered Athens with not only his private army, but accompanied by a six foot alpine Athenian girl representing the Goddess Athena. This fourth dimension he was successful.

Pisistratus maintained Solon'south laws and allowed elections to accept place every twelvemonth. Among his benign actions to Athens was the appointment of rural magistrates enabling all farmers to have access to legal redress. His foreign policy added to the city's prosperity, and he developed peaceful relations with other Greek tyrants. Pisistratus was responsible for the cultural transformation of Athens including the annexation of the island of Delos, which gave Athens control of the prestigious sanctuary of Apollo. He embarked on a building program that included the structure of a temple to Athena on the Acropolis and the temple of Olympian Zeus. He instituted competitive musical and athletic festivals such as the Dionysia and Panathenaia that made Athens an important cultural center of the Greek world.

Fifty-fifty though nobility still governed the metropolis, the Council and People'south Associates could at present challenge whatever corruption of power.

From now on at that place is a strong sense of a government, dominion of police force and regularity in Athens, which leads the fashion to its eventual democratic evolution.

Pisistratus's son Hippias ruled oppressively and was driven out of Athens with assist from the Spartans, who then put a garrison of 700 soldiers in the Acropolis.

Cleisthenes (ca 565–500 BCE).

Cleisthenes drove them out and in one year in office (508–507), offered and gave democracy to the Athenian people. He completely reformed society, mixing people from dissimilar tribes and from the different factions of the Hill, the Shore and the Obviously. He bankrupt up old loyalties, redesigned and enlarged the Council and made the pop assembly the main legislative body. Fifty-fifty though nobility notwithstanding governed the city, the Council and People's Assembly could at present challenge whatsoever abuse of power.

The Classical Period (Circa 500–300 BCE)

Athenian commonwealth became a model and their reforms reverberated throughout the Greek globe.

This period is sometimes described as "the Golden Age" nevertheless it was a time of almost constant strife. It began in 490 BCE with the Persian Wars which Athens was instrumental in winning, and information technology concluded with the Peloponnesian State of war which pitted Athens and her allies confronting Sparta and her allies, and which Athens lost in 404 BCE. Nevertheless in spite of, or perhaps because of, this turmoil, it was an extraordinarily creative time when Axial Greece came into its own, and the great monuments, the art, philosophy, architecture, democracy and literature that nosotros at present value equally the beginnings of our own Western civilization came into being.

During this time, Athenian democracy became a model and their reforms reverberated throughout the Greek world. The middle classes at present participated in council debates along with the nobles and Greek intelligentsia. A new system, which the Athenians chosen isonomia (equal order), now energized the Greeks and encouraged other poleis to try like experiments.

Smaller allied states paid contributions in silver that enabled Athens to expand its shipbuilding and arsenals, and led to Athenian domination of Greek trade.

Uncooperative states were seized and their lands given to Athenian colonists, (cleruchs,) thus Athenian territory expanded. In addition, Athens became a haven for political exiles from other parts of Hellenic republic, people who brought their wealth and expertise, and who set up business ventures in the Athenian land.

Nether Pericles (495–429 BCE) the authority of the Assembly and the Heliaea (people'south courts) was made absolute, the Parthenon, Prophylaea and Erectheum were synthetic, and the Athenian Empire emerged.

Republic and Slavery

Classical Greek Democracy depended on the participation of the greatest number of citizens. Citizens had obligations to the State: to exist part of judicial and political assemblies, to be on jury service, to attend religious festivals and other country activities. Even in their free time they were expected to play the prescribed part of the gratuitous denizen and to pursue activities chosen schole (from which we get our word school). Schole involved regular practise at the gymnasium, attending philosophy lectures and poetry recitals, all of which helped to establish the gratis citizen's superiority. In this style the citizen proved himself fitted to rule.

Citizens were dependent upon the ubiquitous slaves. Nosotros know from the poems of Homer and Hesiod that slaves were part of Greek civilisation since the primeval times, before 700 BCE. In the later Classical period, even the poorest Athenian citizen would own a slave, and not owning one meant that you were practically destitute. Slaves worked businesses, assisted the citizen women, who were nearly confined to their private homes nevertheless in charge of domestic problems, and performed tasks for the State. Their work included performing clerical jobs, removing refuse and dung from the streets, and dangerous tasks like silverish mining in Laurium. Their work provided invaluable wealth to the citizens and the state.

Greek commonwealth and culture depended on the ownership of slaves and Greek citizens establish a style to justify information technology.

Ownership of land was yet commended, and farming one of the most desirable sources of wealth, but the labor information technology required was not valued and where possible was performed by slaves.

In summary, Greek republic and civilization depended on the ownership of slaves and Greek citizens found a way to justify it. The obligations of citizenship and the regular activities of schole where the gratuitous man cultivated his mind, soul and physical excellence, proved his superiority. Conversely, those who labored and did not cultivate their listen were inferior. They were fit but for piece of work and deserved to be slaves.

Thucydides and the Beginnings of History (Circa 460–395 BCE)

Bosom of Thucydides residing in the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto.

Past the 2nd half of the 5th century Athens and Sparta emerged as the two nearly powerful states in Greece. Merely now without a common enemy, tensions grew between them, and in 431 BCE they confronted one another, with most of the Greek states joining in support of either state. This Peloponnesian War was a long and merciless civil slaughter that, over twenty-vii years, produced suffering on a scale previously unknown to the Greeks. By 404 BCE Spartans had destroyed the Athenian navy, dissolved the entire empire, marched into Athens, and a pro-Spartan oligarchy ruled the Athenians. Athenian democracy was suspended and a pro-Spartan oligarchy – the Thirty – was installed.

This Peloponnesian War was a long and merciless ceremonious slaughter that, over twenty-seven years, produced suffering on a calibration previously unknown to the Greeks.

Almost the entire state of war was witnessed past Thucydides (465–395 BCE), a well educated member of the Athenian elite and one of the virtually important and influential historians, whose writings are all the same studied and discussed in military colleges today.

Before Thucydides, Herodotus had written history as one would and then tell a good story: with a focus on notable events that included heavenly and cosmic intervention.

Thucydides saw that human behavior, not the Gods, was responsible for these events. He attempted to clarify events in a manner that would help people sympathize that they were non a event of the gods' favor or disfavor, but of the actions of individuals. We are all subject field to passions, desires and appetites; mostly, we go to state of war for irrational reasons, state of war is a "Harsh master and a harsh teacher," it destroys our better natures which are nurtured by law and custom. Duress brings out our worst characteristics, and these are evident as war becomes protracted. Fathers kill their sons, neighbors their neighbor, his family and livestock.

Thucydides felt human nature was predictable and didactics, religion, regime and family were ways to assistance us ascent above our natural selves.

He felt that the power of Athens had alarmed the Spartans plenty to be a major cause of the state of war, and looked for the underlying causes of disastrous events in wartime, such as fear, pride, bad calculations, or indecision. His accounts illustrated the way homo affairs e'er follow the same patterns, among them: that power always seeks to increase; that necessity is the engine of history; that leaders must impose their will on those they lead, and that weakness invites the domination of the stronger entity.

Thucydides felt man nature was anticipated and education, faith, government and family were ways to assistance us rising above our natural selves. People will behave in the same way under the same circumstances unless it is shown to them that such a form, in other days, ended disastrously. Athenians lost considering they were incompetently led by people who, hungry for power and unscrupulous, misunderstood the strength of the Farsi influence, and were undermined past their ain greed and hubris.

Internal Wars and Philip of Macedon (338 BCE)

During the fourth century, after the defeat of Athens by Sparta, the Greek states remained mired in wars, supported in office by Persian satraps (regional governors) interested in destabilizing Sparta. Resentment against Spartan hegemony united erstwhile enemies and even allies. Eventually in 379 BCE Athens resumed its position as the leading Aegean power past calling on allies and boosted formally pro-Spartan states, and reviving the Athenian League. In 371 BCE the Spartans were defeated at Leuctra in Thebes, which and then became the dominant state, but not for long. States allied themselves against Thebes, and from and so on continually disputed among themselves until they were overshadowed by the foreign invasion of Philip of Macedon in 338 BCE.

This endless strife continued to exist the properties to cultural innovation and activity in the polis (urban center state).

The Pre-Socratic Philosophers

These innovative thinkers came from both the eastern and western regions of the Greek globe. Only fragments of their original writings survive, and our information nearly them comes from afterwards philosophers such every bit Aristotle, who called them "Investigators of Nature".

They used prose not poetry as their language of inquiry, and gradually prose became associated with the linguistic communication of investigation, and logos to represent what we would telephone call scientific inquiry.

Just as questions, debate and reasoned solutions were function of political discussions in the Greek polis, these men focused on speculative questions, discussions, argue and reasoned conclusions with regard to the nature of the earth. They thought of themselves every bit philosophers (literally "lovers of wisdom").

Rather than rely on supernatural answers, they sought the natural elements that were involved in the world's formation (physis), and to identify the Eunomia (balance) of the universe and the principles governing it. Their questions fell into areas that nosotros now categorize as science, philosophy and spirituality. They used prose non poetry as their language of research, and gradually prose became associated with the language of investigation, and logos to stand up for what we would call scientific inquiry. From this sense of the give-and-take we get "logic" – rational thinking.

In the kickoff half of the sixth century, the Ionian city of Miletus was a rich trading center with numerous colonies, possibly the most powerful Greek urban center on the coast of Asia Minor (modern twenty-four hours Turkey). Its citizens were audacious sailors whose travels took them to the cultures of Mesopotamia and Arab republic of egypt and who lived shut to the rich city-state of Lydia.

Thales of Miletus (Circa 624–547 BCE)

Thales

It was the Ionian mathematician and astronomer Thales, whom Aristotle called 'the founder of natural philosophy', who prepare the Milesian school and so launched the beginning of philosophy and scientific discipline. Thales was from a wealthy family in Miletus whose father may have been of Phoenician ancestry. He was a contemporary of Solon and had likewise traveled and studied in Egypt, where he may well have learned some of the mathematical discoveries with which he is credited. Thales was widely believed to have predicted the solar eclipse in 585 BCE. He was a highly successful businessman and statesman, as well every bit a mathematician who is said to accept claimed his only interest in business was to demonstrate the applied advantages of clear thinking.

Never before had someone put forward general ideas and explanations about the nature of the world without recourse to religion or myths. For the offset time there was a conviction that in that location were natural laws controlling nature, and that these laws were discoverable. The world is made of material, and information technology is governed by the laws of material motion. Thales did not break entirely with religious explanations but he did endeavour to give rational explanations for physical phenomena, challenge that backside the phenomena was not a catalogue of deities, just 1 single, kickoff principle, which he chosen an archê, "crusade". He identified this beginning principle as water.

Anaximander (Circa 611–547 BCE)

He was Thales' student and was the outset to write a treatise in prose, which is known traditionally as On Nature. This has been lost, although it probably was available in the library of the Lyceum at the times of Aristotle and his successor Theophrastus. He explored the notion that there was a single, imperishable, principal element, but he disagreed with Thales over what it was. It was hard to meet how h2o could be contained in something that is very dry, for instance, and Anaximander went on to reason that the primal material must exist something that transcends ordinary thing, all of which would have limitations like to the water theory. Therefore he postulated that the cardinal cloth must be something imperceptible to our senses that encompasses even properties of matter that appear opposite from each other. Anaximander identified this with 'the Boundless' or 'the Unlimited' (Greek: 'apeiron', i.e. 'that which has no boundaries'). Information technology lay across our feel, it was beyond the Gods, and the source of all life.

Another Milesian, Anaximenes (ca 585–525 BCE), said the primary element was air.

Analogy of Anaximander's models of the universe.The sun, moon and each of the stars is really a transparent band – or hoop – made of air. Each band is filled with fire which we can only see when the hole in that detail ring passes over us. On the left, daytime in summer; on the right, night in winter.

Pythagoras (Circa 582–504 BCE)

Bust of Pythagoras of Samos in the Capitoline Museums, Rome.

He was active in southern Italy towards the terminate of the sixth Century. He coined the term "lovers of wisdom" (philo-sophia) saying that some people seek wealth, some power and adoration, and some fame, but the wisest are those who pursue knowledge: the philosophers. He wrote nil down and apparently discouraged writing, and so nosotros have no original documentation. Notwithstanding, his ideas reflect the vision of Axial Historic period thinkers in other parts of the world. In other words, it appears that he and his pupils' primary quest was for spiritual enlightenment.

Pythagoras was well-traveled. As a young man he studied with both Anaximander and Thales of Miletus. He was said to have been initiated into the aboriginal mysteries of the Phoenicians studying in the temples of Tyre, Sidon, and Byblos in modern day Lebanon, and to accept visited Haifa and the temple on Mount Carmel in State of israel. He spent time studying in Arab republic of egypt, and when the Persian Empire expanding westward, invaded that land, he was captured along with members of the Egyptian priesthood and taken to Babylon. In Babylon he would have institute himself at the eye of a convergence of religious and philosophical ideas, and in a civilization that, similar Arab republic of egypt, was also at the forefront of mathematics and astronomy. Zoroastrianism was in its early days, the Magi (Zoroastrian priests) were establishing the ethical teachings, rituals and monotheism of their religion in contrast to the multiple gods and rigid social hierarchy that was already part of Babylonian culture. Here Pythagoras may well have studied the importance of numbers and of the interaction of contraries or opposites – good/evil; positive/negative; light/dark; right/wrong; etc.

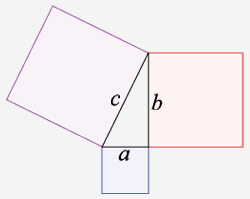

The Pythagorean theorem: The sum of the areas of the two squares on the legs (a and b) equals the expanse of the foursquare on the hypotenuse (c).

Later twelve years in Babylon, he was allowed to return to his birthplace, Samos in Ionia. Leaving Babylon, he may well have traveled through Persia into Bharat to continue his education where some sources say he is referred to as Yavanacharya, the "Ionian Instructor". He could well take obtained his Karmic ideas direct from India, although like ideas were likewise known in Egypt, plus, in Greece, the Orphic cult was heavily influenced by Eastern belief, particularly on the transmigration of the soul.

He intended to set a community in Samos but corruption, fail and tyrannical oppression made it unsuitable. He journeyed to Croton on the east of Italy, where he founded the Pythagorean society of philosophy, mathematics, and natural sciences. People from different classes – and fifty-fifty women – came to his school to hear his lectures and go part of his community. He recommended modesty, austerity, patience, equality and self-command.

Pythagoras'south famous saying "All is number" refers to his understanding that beyond the world of appearances there lies an abstruse harmonious world of number. For the first time he demonstrated that the construction of nature is translatable into numbers and geometric forms which tin draw its primal laws.

John Strohmeier and Peter Westbrook write in their book Divine Harmony – The Life and Teachings of Pythagoras, "For Pythagoras, mathematics served as a bridge between the visible and invisible worlds. He pursued the discipline of mathematics not simply as a way of agreement and manipulating nature, but also as a means of turning the mind away from the physical world, which he held to be transitory and unreal, and leading it to the contemplation of eternal and truly existing things that never vary. He taught his students that by focusing on the elements of mathematics, they could calm and purify the mind, and ultimately, through disciplined try, feel truthful happiness."

Heraclitus of Ephesus (Circa 535–475 BCE)

Heraclitus (right) by Johannes Moreelse. The image depicts him every bit "the weeping philosopher" wringing his hands over the world and "the obscure" dressed in night article of clothing, both traditional motifs.

He was a student of Pythagoras. He wrote that "all is flux," that truth lies in constant alter, in the impermanence of nature as illustrated by the proverb attributed to him: "No man steps into the aforementioned river twice". Yous could not rely on the bear witness of your senses, you needed to get deeper in order to find unity. At the foundation of this perpetual flux experienced by both human beings and nature was the ruling principle – logos.

Xenophanes (Circa 560–480 BCE)

He went to Elea from Asia Pocket-sized where he founded the Eleatic School. Past this fourth dimension, people now realized that political institutions could be changed without causing any reaction from the Gods, and some now began to question their beingness. Xenophanes ridiculed these anthropomorphic gods, he believed in one bully God, which was not concrete but was all mind (in Greek: nous), moving all things by the force of his spirit without himself having to motility.

Parmenides of Elea (Circa 520–450 BCE)

Parmenides. Item from The School of Athens by Raphael.

He was a student of Xenophanes. He taught that reality was one complete, eternal, quintessential Being beyond fourth dimension and change, and that the changing world registered past our senses was an illusion.

Anaxagoras of Athens (Circa 500–428 BCE)

He taught that all things come up to be from the mixing of innumerable tiny particles of substance, shaped and controlled by a creating principle he called Nous ("Mind"), a divine intelligence.

Leucippus (5th century) and Democritus (Circa 460–370 BCE)

They argued that everything was fabricated upwards of an space number of tiny, invisible particles which they called "atoms." Democritus named the atom after the Greek word atomos, which means "that which can't be divided further." As they motility in infinite infinite, these atoms combine with others into an innumerable multifariousness of shapes, forming, among other things, what nosotros see and know of the world. Human's actions are no exception to this universal law, and gratuitous-volition is a mirage.

Epicurus (341–270 BCE)

Etching of Epicurus.

Similar Democritus, Epicurus also taught that the universe was made of tiny indivisible units, or atoms, moving in space space. Everything that occurs is the outcome of these atoms colliding, rebounding and joining with each other, in a incessant process of cosmos and destruction. Plants, animals and humans evolved randomly over ages, some forming species that survive for a time, simply nothing lasts forever. Only atoms are immortal, so every phenomenon is the outcome of natural causes. The atoms in the void, obey the constabulary of their own natures, falling down because of their weight, coming together and clashing, forming molecules and larger masses, and, ultimately, building upwardly the whole universe of worlds in infinite infinite.

In this view then, there is no need of gods, who are similarly created only are unconcerned with human being affairs, and then should not be feared. Neither should death be feared since it is only the dissolving of the atoms that make up the trunk and soul.

Withal, Epicurus' philosophy differed from the earlier atomism of Democritus in that he believed that our senses are infallible and, through them, we know that we accept gratuitous will. If man's will is free, it cannot be by special exemption to the natural laws of atomic materialism, only because of some inherent principle: some element of unconscious spontaneity in the atoms' behavior. Epicurus conclusion was that they randomly swerved. " Information technology is the 'swerve' then which enables the atoms to meet in their downward fall, information technology is the 'swerve' which preserves in inorganic nature that curious element of spontaneity which we phone call run a risk, and it is the 'swerve', become conscious in the sensitive amass of the atoms of the mind, which secures man's freedom of activeness and makes it possible to urge on him a theory of acquit." Titus Lucretius Carus, Lucretius On the Nature of Things, trans. Cyril Bailey.

This conduct should exist guided by each individual's perception of pleasance and pain, experienced in both body and soul. Pain is the dislocation of diminutive arrangements and motions, pleasance their readjustment and equilibrium. Epicurus' objective was to attain a counterbalanced, tranquil life, characterized past ataraxia—peace and freedom from fear—and aponia—the absence of pain. Pleasure to Epicurus was attained when one is free from either want or pain: when both take been removed.

His extensive writings were mostly lost and suppressed by Christian and Jewish theologians to the extent that the English definition of Epicurean means indulgence in sensual pleasures, especially eating and drinking, and his name is one of the words for heresy in Hebrew. His works survived mostly because of a 7,400 line poem about them, On the Nature of Things by the Roman poet Lucretius.

Some of Epicurus' teachings include:

"Death is nothing to united states. When you lot are dead you will not care, because you will not be."

"All organized religions are superstitious delusions rooted in longings, fears, and ignorance."

"The greatest obstacle to pleasure is not pain; it is mirage. The enemies of human happiness are inordinate want—the fantasy of attaining something that exceeds what the finite mortal world allows—and gnawing fearfulness."

The Sophists

Equally role of the scientific revolution in the fifth century BCE a new form of teachers appeared, who taught epistemology, linguistic communication, geometry, astronomy and biological science, and to a higher place all, rhetoric and eristic, the study of argumentation. Anyone who wanted a position of importance, especially in a democracy, would have to have oratorical skill, strength in debate, and a knowledge of law and politics; one would need to know how to manage property and mayhap run the state, and know something of music, astronomy, math, physics, and so on. The Sophists equipped one to exist a leading denizen, and supplied answers to help people alive in a world whose reality had now been somewhat undermined by the Pre-Socratics.

Greek Drama

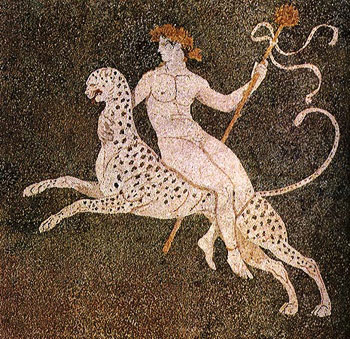

By the finish of the sixth century, Athens had go the home of a tradition of drama that strengthened the bonds of the unabridged community. The City Dionysia, was held in March each year to welcome the spring. Dionysus, amongst other things, was the God of tragic art, and some scholars believe that these events were part of the religious festival in his award. Others that they were added to the religious festival since the "audition" had already gathered for that event. Nevertheless, gods are always present in the plots, at least in the background, and sometimes as characters on the stage. They are often invoked, or challenged by the human heroes who are frequently their helpless pawns.

Dionysos riding a leopard, 4th century BCE mosaic from Pella.

The plays took identify in a stadium that seated well-nigh 20,000 people and were held on three specific and consecutive days each year, from sun upwards to lord's day downward.

Each day one poet alone would present a trilogy, followed by a caricatural satyr play, which was shorter and often connected thematically to the plays that preceded information technology. In the Greek agonistic spirit — (from the Greek agōnistikos, from the word agōn meaning contest) — these plays were role of a competition between three tragedians selected for the event by the Archon responsible for organizing it all. In addition, more frequently than not, the master characters in every play were in disharmonize with each other.

The Theatre of Dionysus (above) in Athens.

Tragoidia is a formal term that refers not to the subject thing but to the form, and its meaning was more like our word "play" than our word "tragedy." Co-ordinate to Aristotle, "The plot of a Tragoidia needed to exist serious." Even so, those that survived are about all tragedies in our sense of the word.

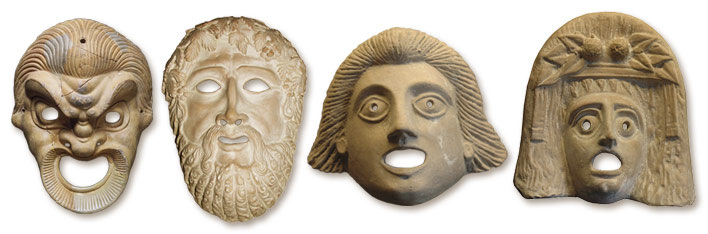

Actors were generic figures: they wore heavy masks, hiding any expression, their robes were heavy and indistinguishable from each other, their movements ritualized. To move the audience, they relied entirely on the quality of their voices, dance-like movements, and on the verse they spoke and sang. Sophocles, for instance, avoided performing in his plays because his vocalization was too weak.

The plots were almost always fatigued from traditional Greek mythology and tended to focus on disharmonize within a smashing family from the remote and heroic past. So the broad outline of the story and the principal characters would be known to the audition. But the play's details were modified, and small characters frequently invented in order to refocus the story to highlight whatsoever angles the writer wanted, putting whatever words he wanted into the character'south mouths. Thus the tragedy commented on wider contemporary social themes, like justice, the tension between public and private duty, the dangers of political ability, and the balance of ability between the sexes.

Greek audiences would already be accustomed to mind attentively for a long fourth dimension in public assemblies, and in the law courts, consequently the spoken word would have been easier for them to listen to and retain than this format would exist for u.s.a. today.

Aspects, perspectives and the relevance of the trilogies would be discussed past citizens, since tragedy not but validated traditional values, reinforcing group cohesion, only likewise exposed weaknesses, conflicts and doubts in both the individual and the state. Athenian republic was new and the transition from traditional blood or tribal loyalty to loyalty to the state, although intellectually welcomed, would probable have been more difficult for individuals to internalize. Athenians applied what they learned in the theatre to other aspects of their lives, to difficult borough issues, to their deliberations in the Assembly and to their judgments in the courts.

The plays told stories that dealt ruthlessly and relentlessly with human passions, conflicts and suffering at the same time expressing Greek ideals. They were open to all citizens, possibly even women and slaves. Over at least three days, then, Athenians had the opportunity and infinite to experience and think about those aspects of humanity that threatened the wellbeing and eunomia (balance) of their society, both in the oikos (family unit) and in the polis (state.)

Here in open-air theatres the public could watch as every transgression—even the well-nigh horrific of human drives and passions—was acted out and released in a very controlled setting. It provided a cathartic experience (or cleansing) for everyone; here suffering was experienced and accepted, and empathy fostered. Greek Classical Theatre was a safety valve for the society where every year, passions and concerns were revealed so could be controlled.

Karen Armstrong writes inThe Great Transformation, "Tragedy taught the Athenians to project themselves toward the 'other' and to include within their sympathies those whose assumptions differed markedly from their ain. … In a higher place all, tragedy put suffering on phase. Information technology did non allow the audience to forget that life was 'dukkha,' painful, unsatisfactory, and amiss. By placing a tortured private in front end of the polis, analyzing that person's pain, and helping the audience to empathize with him or her, the fifth-century tragedians – Aeschylus (ca 525 – 456), Sophocles (ca 496 – 405), and Euripides (ca 484 – 406) – had arrived at the centre of Centric Age spirituality. The Greeks firmly believed that the sharing of grief and tears created a valuable bond betwixt people. Enemies discovered their common humanity …"

Greek theater masks: comedy, Zeus, youth and Dionysus.

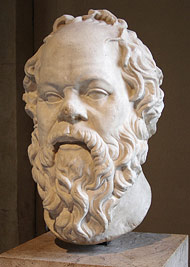

Socrates (470–399 BCE)

Bust of Socrates.

Karl Jaspers writes inThe Great Philosophers, Vol. 1,"His mission was simply to search in the company of men, himself a man amongst men. To question unrelentingly, to expose every hiding place. To demand no faith in annihilation or in himself, but to demand thought, questioning, testing and then refer man to his own self. But since human's self resides solely in the noesis of the true and the practiced, only the man who takes such thinking seriously, who is determined to be guided by the truth, is truly himself."

The objectives of this rigorous, lengthy and relentless dialogue were to demonstrate the limits of a pupil'due south … ability to get in at existent knowledge in this way, and to expose the student's assumptions

"Let it be clear to y'all that my relationship to philosophy is a spiritual one." Socrates says at his trial. His instruction method, known as elenchus (cross-examination), is often thought to be designed to draw out the educatee's innate cognition through a series of meticulous, rational, questions and answers. This describes the procedure but its purpose was more than a search for innate noesis as we generally empathise it. It is more likely that the objectives of this rigorous, lengthy and relentless dialogue were to demonstrate the limits of a educatee's – or anyone'south – ability to arrive at real knowledge in this mode, and to betrayal the educatee's assumptions, opinions and false beliefs in order that that he or she might eventually realize that there was no correct answer. Through this confusion the private would run into that he or she really knew nothing at all, at which betoken the search for truth could begin. Finally, by questioning their nearly central assumptions, and through unrelenting questions and answers, individuals would be able to access an intuitive power – a change in consciousness – and perceive ultimate skilful.

In Theaetetus Socrates describes himself as a midwife, guiding each student to notice inside himself a level of intuitive understanding and self-noesis that was synonymous with virtue.

In 399 BCE Socrates was accused of two violations of Athenian law: blasphemy past instruction near new gods non recognized by the Athenians, and corrupting the youth of Athens.

Like Pythagoras, the Buddha, and many other teachers, Socrates wrote nothing down, resisted formulating a coherent philosophical path and had no dogma. He was aware that some students, at least initially, were merely entertained by practicing his method, but he knew otherwise: "They enjoy hearing men cross-examined who remember they are wise but they are not. Just I maintain that I have been commanded by the God to do this through oracles, through dreams, and in every way in which some divine influence or other has always commanded man to exercise anything." writes Plato in The Apology.

In 399 BCE Socrates was accused of two violations of Athenian law: blasphemy by educational activity near new gods not recognized past the Athenians, and corrupting the youth of Athens. He was accused of teaching young men idleness and encouraging cultish behavior. But possibly higher up all – when the great Athenian Empire was losing to the Spartans towards the end of the Peloponnesian War – he was, in a sense, a scapegoat for their shame, disliked considering he numbered amid his friends and students men who were perceived as enemies of the Athenian State, such as Alcibiades and Critias. (Alcibiades had, on several occasions, changed sides, and Critias became part of the pro-Spartan oligarchy installed subsequently Athens lost the state of war in 404 BCE.) In improver, his dialectic method – whereby through rigorous questioning he lead people to see the fallacy and limits of their thinking – made many conclude that he was only intent on making them feel inferior.

Even in defending himself at his trial, Socrates revealed that first and foremost he was a teacher. "I shall never cease from the practice of philosophy, exhorting anyone whom I run into and maxim to him after my mode: You lot, my friend … are you non ashamed … to intendance and then little about wisdom and truth and the greatest improvement of the soul, which you never regard or heed at all?" Instead of offering a defence that would assure his release, he refused to compromise and used the opportunity to expose the shallow emotionally-driven thinking of the members of the judiciary: "For if you kill me, you will not hands detect another similar me, who, if I may utilise such a ludicrous figure of speech, am a sort of gadfly, given to the city by God … [Merely] you may feel out of temper like a person suddenly awakened from slumber and might suddenly strike me dead … and then slumber on for the remainder of your lives, unless God in his care for you lot sends someone to take my place."

When the possibility of escaping from jail was presented to him, Socrates used this every bit an opportunity to teach Crito to observe the effect and consider the consequences of one'due south actions, thoughts and feelings. In this instance such an action would in a sense destroy the Athenian state, whose laws had permitted his nascency, upbringing and education and of which he willingly chose to be a citizen, obedient, therefore, to its laws. Socrates, in a lengthy dialogue, takes the role of the land and determines that if he did not stand by this understanding now, he would be dishonored, and his friends suffer by association.

"[Man] has only one thing to consider in performing any action – that is, whether he is acting rightly or wrongly…"

Socrates had no fear of expiry: "You are mistaken, my friend, if y'all think that a human who is worth anything ought to spend his time weighing upwards the prospects of life and death. He has only one affair to consider in performing any activeness – that is, whether he is acting rightly or wrongly… . No 1 knows with regard to death whether it is not really the greatest blessing that can happen to man, but people dread it equally though they were certain that it is the greatest evil, and this ignorance, which thinks that information technology knows what it does not, must surely be ignorance well-nigh culpable."

So he drank the hemlock and was put to death as the Country required. "Such, Echecrates, was the end of our friend, who was, we may fairly say, of all those whom we knew in our fourth dimension, the bravest and likewise the wisest and nigh upright man." says Crito at the finish

of Phaedo.

The Decease of Socrates, by Jacques-Louis David (1787).

Xenophon

He was a pupil of Socrates and would later record a number of Socratic dialogues as well equally personal accounts of Socrates, whom he admired greatly. His prose included not simply histories, but biography, political pamphlets, and instruction manuals on an array of subjects, including household management, hunting and military tactics. He is oft called the original "horse whisperer", having advocated sympathetic horsemanship in his treatise "On Horsemanship".

Plato (428–347 BCE)

The most of import thinker to follow Socrates was his pupil Plato.

He was an aristocrat, his mother was descended from Solon, and father from the last king of Athens, Codrus. Unlike his mentor Socrates, Plato was a prolific writer besides as a teacher. A devoted pupil of Socrates, three of his early dialogues – The Apology, Crito, and Euthyphron – plus the after Phaedo are devoted to the trial, prison days, and ultimate expiry of his instructor.

Afterwards the decease of Socrates, Plato, disillusioned with political life, traveled in Egypt and Italy for approximately x years. He fabricated contact with the followers of Pythagoras, whose understanding that numbers and geometric forms provided a way in which to understand reality, stimulated his ain Theory of Ideas (of Forms).

In 387 BCE Plato founded the Academy in Athens which lasted in one form or another for nine-hundred years until 527 AD. Plato and other teachers instructed students from all over the Greek world in metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, politics, natural and mathematical sciences. Although the University was not meant to gear up students for any sort of profession, members of the Academy were invited by various cities to help in the evolution of their new constitutions.

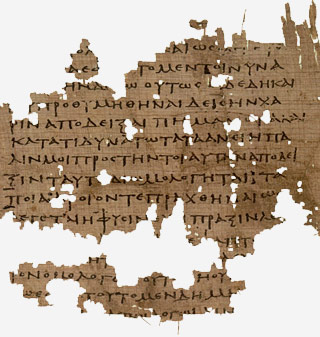

Around 390 BCE Plato is thought to have written The Republic. He did this in office to claiming the prevailing attitudes of the Sophists, the hired teachers that instructed the sons of Athens at this time, who were pedagogy a subjective morality that went something similar this: whatever is to one'south advantage should be engaged in, and whatever is not, should be avoided. They considered any other morality a mere convention, insisting that the strong have reward over the weak, and concepts of objective justice or objective truth were merely the products of propaganda and the tools of oppressors.

Papirus Oxyrhynchus, with fragment of Plato's Democracy.

Perhaps the most famous extract from Plato's piece of work is in Book VII of The Commonwealth, where he describes his ideas in the form of an apologue. In a dialogue between Socrates and a student named Glaucon, The Allegory of the Cavern, provides a poignant image of human beings who, although ignorant of their status, are, since childhood, imprisoned in a cave, chained and able only to face direct alee. Unable to motion, in that position they tin see merely the shadows of what is backside them reflected on the cave walls in front, and tin can hear only echoes of real voices. Knowing nothing else, these shadows and echoes seem to them to be real, every bit appearances are real to united states of america.

Towards the end of the allegory, Plato refers to the demise of his old master when, as Socrates, he asks us to consider what it might be like if someone who had seen reality came dorsum down into the cave. What, he asks, would the people retrieve of him? He would inevitably be misunderstood and would become a laughing stock. If, in addition, he tried to set the convict men free and have them to the low-cal, "if they could somehow go their hands on him and kill him, wouldn't they exercise just that?" Glaucon agrees that they would.

The earth revealed past our senses is non the real world but only a poor copy of it.

And so Plato, equally Socrates, farther reveals the significant of this allegory and his own philosophical agreement: "That is the picture so my beloved Glaucon, and it fits what we were talking about earlier in its entirety. The region revealed to u.s. past sight is the prison dwelling and the calorie-free of the fire inside the home is the power of the lord's day. If you lot identify the upward path and the view of things above with the rise of the soul to the realm of understanding, and then you will take caught my drift, my surmise, which is what you wanted to hear. Whether it is really true, perchance only God knows. My own view, for what it is worth, is that in the realm of what tin can be known the matter seen last and seen with corking difficulty is the course, or character of the proficient. Simply when information technology is seen, the conclusion must be that information technology turns out to be the cause of all that is right and expert for everything. In the realm of sight it produces light and light'south sovereign, the sun, while in the realm of idea it is itself sovereign producing truth and reason unassisted. I further believe that anyone who's going to act wisely either in private life or in public life must take had a sight of this form of the adept."

The world revealed by our senses is not the existent world merely only a poor copy of information technology. The existent world tin can only be apprehended through the effort of rational thought. Justice was rational, and people needed to be brought upward in a guild governed by reason. Enlightened individuals, in Plato's view, had an obligation to the rest of society to serve information technology. Social club in lodge to be good should be ruled by them – the truly wise Philosopher-Kings.

[Plato] argued that all conventional political systems were inherently corrupt, and therefore the state ought to be governed past an elite class of educated philosopher-rulers…

Plato says in The Laws, "We should keep our seriousness for serious things and not waste matter it on trifles, and … while God is the real goal of all beneficent serious endeavor, man … has been constructed equally a toy for God, and this is, in fact the finest affair nearly him. All of us, so, men and women akin, must fall in with our role and spend life in making our play as perfect as possible."

Axial Age Greece was approaching its cease, and, unlike the teachings of typical Axial teachers, Plato's utopian city was elitist and lacked compassion. He argued that all conventional political systems were inherently corrupt, and therefore the country ought to be governed by an elite form of educated philosopher-rulers, who would be trained from birth and selected on the basis of aptitude.

Always seeking a practical awarding of his ideals, he identified justice as presiding in the construction of this platonic metropolis where its functions are implemented through specialization: anybody does what he is best fitted to do and you have a simply city. Similarly in the individual – in a just soul, at that place is a correct balance between the parts: the rational part must dominion and dictate the overall aims of the human being, the emotional role must enforce the rational parts convictions, and the appetitive part must obey.

Plato claimed that since our experiences were unreal compared with the world of the Forms, people should devote themselves to understanding the reality of the Forms which they could do if they applied themselves, through discipline and rational thought. He disapproved of poetry, music and theatre, which were part of traditional Greek didactics, because these things aroused irrational emotions and encouraged people to give in to them; they encouraged immoderation and sympathy, both of which were incompatible with virtue in Plato's view. Life was sometimes miserable, but it was non real, and information technology was only possible to ascend to the real world through self-controlled, disciplined and rational behavior.

Karen Armstrong says inThe Great Transformation, "At the start of his philosophical quest, Plato had been horrified by the execution of Socrates, who had been put to death for teaching imitation religious ideas. At the terminate of his life, he advocated the capital punishment for those who did not share his view. Plato's vision had soured. It had go coercive, intolerant, and castigating. He sought to impose virtue from without, distrusted the compassionate impulse, and made his philosophical organized religion wholly intellectual. The Axial Historic period in Greece would make marvelous contributions to mathematics, dialectics, medicine, and science, but it was moving abroad from Spirituality."

Plato's University would eventually become the model for the Western university.

Aristotle (384–322 BCE)

Plato (left) and Aristotle (right), a detail of The School of Athens, a fresco past Raphael.

Plato's student Aristotle studied at the Academy for near twenty years, leaving after Plato's death, in 347 BCE. Iii years later he was invited by Philip Two of Macedon to get the tutor to his son Alexander the Keen, which he did for at least another three years before traveling to Asia Minor where he went with Theophrastus to Lesbos to enquiry the botany and zoology of the island. He finally returned to Athens where he established his own school, known every bit the Lyceum and taught there for twelve years.

Every bit a well-known quote has information technology: "To Plato all chairs are but junior forms of the perfect chair. To Aristotle if yous add up all the unlike types of chair and reduce them to their mutual denominator, then you would sympathize what a chair is."

Plato's philosophy of Forms would have been familiar to Aristotle's students, merely like the pre-Socratic philosophers before him – those he called the "Investigators of Nature" – Aristotle encouraged his students to await at what was in front of them, to seek the nature of those forms and the principal instances of them as they exist right here in the globe. Aristotle believed that the search for wisdom should brainstorm with the sense perceptions and that through these we tin can acquire the understanding of both facts and causes, and the universal principles and primary causes on which they are built. His approach was strictly empirical, through observation, classification and deductive reasoning nosotros would come to understand the causes and characteristics of things.

Aristotle became extremely critical of the notion that the ideal world was more real than the material universe, and questioned the independent objective existence of Forms. To him qualities of beauty, courage, roundness, etc. existed simply in the cloth objects themselves.

"…the Forms …are non the causes of motion or of any other change …And they do not in whatever mode assistance either towards the knowledge of the other things …or towards their existence …Moreover, all other things practise not come up to be from the Forms in whatever of the usual senses of "from." And to say that the Forms are patterns and that the other things participate in them is to use empty words and poetic metaphors." says Joe Sachs, St. John's College, Annapolis.

He describes the Unmoved Mover as existence non-matter, perfectly beautiful, indivisible, and contemplating merely the perfect contemplation of itself contemplating.

Aristotle and his students nerveless data on any and all aspects of the physical globe and proceeded deductively to form theories and conclusions from the largest amount of information possible. He non merely studied about every subject possible at the time, simply fabricated meaning contributions to most of them. In concrete science, Aristotle studied anatomy, astronomy, economics, embryology, geography, geology, meteorology, physics and zoology. In philosophy, he wrote on aesthetics, ethics, government, metaphysics, politics, psychology, rhetoric and theology. He also studied educational activity, strange customs, literature and poetry.

Aristotle's work in metaphysics was motivated by a want for wisdom, which requires the pursuit of noesis for its ain sake. Through observation and logical reasoning Aristotle arrived at the concept of the Unmoved Mover: one can observe that there is motility in the world, that things that movement are set in motion by something else, there tin be a chain of movement, but there must be something that caused the very get-go motility. This first cause gear up the universe into motion, it is not moved past whatsoever prior action but by desire. He describes the Unmoved Mover equally existence non-matter, perfectly beautiful, indivisible, and contemplating but the perfect contemplation of itself contemplating. Mod physics has proven his premise to exist wrong, but to Aristotle this was a rational thought arrived at through deduction and logic.

Karen Armstrong says inThe Great Transformation , "Aristotle was a pioneer of bang-up genius. Nigh single-handedly he had laid the foundations of Western science, logic, and philosophy. Unfortunately, he also made an indelible impression on Western Christianity. Always since Europeans discovered his writings in the twelfth century C.E., many became enamored of his rational proofs for the Unmoved Mover – actually one of his less inspired achievements. Aristotle's God, which was not meant to be a religious value, was foreign to the main thrust of the Axial Age, which had insisted that the ultimate reality was ineffable, indescribable, and incomprehensible – and yet something that human beings could experience, though not by reason. But Aristotle had set the West on its scientific course …."

Source: https://humanjourney.us/ideas-that-shaped-our-modern-world-section/axial-age-religions-greece/

0 Response to "In What Way Are the Teachings of Plato Reflected in the Art and Architecture of Ancient Greece"

Post a Comment